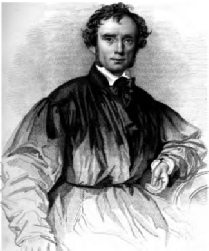

Charles Reece Pemberton.

“The Wanderer”

From "Recollections of Remarkable Persons,”

by Dr. Spencer Hall, in the Manchester Weekly Times

At fifteen he was bound apprentice to an uncle at Birmingham ; but for manufacturing or mercantile life his nature was all unfit, and at seventeen a painful incident closed his connection with it.

At fifteen he was bound apprentice to an uncle at Birmingham ; but for manufacturing or mercantile life his nature was all unfit, and at seventeen a painful incident closed his connection with it.

He was one day sent to purchase some stamps ; his mind was not sufficiently intent on the transaction, and the stamp-

He was afterwards sure that his uncle believed him innocent, and that he ought to have said so, as it might have saved him from years of misery ; but the grievance rankled, and shortly, breaking the tie of his apprenticeship, he ran away.

Ran away ! And the soul that was too sensitive for a Birmingham counting house soon found itself enslaved on board a ship of war ; for at Liverpool he was kidnapped by a press-

He married a lady of great beauty and talent, and anticipated a life of domestic happiness ; but the marriage was not fortunate, and his promised joy proved his certain misery. They had one son, of whose fate I am ignorant. His desire for change of scene returned — if it had ever left him — with the departure of his heart's dear hopes. He was without house and without home, and roamed all the world over. He was acquainted with all classes of society, as well as with all coasts of country ; and was subjected to all manner of vicissitudes. He became, emphatically, A wanderer."

The following incident will give some idea of the character and distance of his wanderings. Being one morning (it was in 1845) at breakfast with Mr. Flower, late mayor of Stratford-

It does not appear very clear when he returned to England ; but in 1832 he was lecturing and acting in some of the provincial towns, when Talfourd (afterswards Judge), then on the Western Circuit, saw him perform at Hereford, and was so influenced by his representations of Skylock and Virginius, as to speak of him in terms of high admiration in an article in the New Monthly Magazine. This led to his appearance at Covent Garden, when London criticism on his performance was as various as London criticism was sure to be ; but in glancing back it is easy to see that the papers most remarkable for independence and taste spoke most warmly in his praise. Still, he did not long remain on the London boards-

Whatever the cause, he seemed thenceforth to prefer the platform to the stage, and appeared in various parts of the kingdom as a lecturer on elocution and the drama. He had also become a contributor of his celebrated " Pel Verjuice" and other papers to the Monthly Repository, edited by Mr. W. J. Fox; and it was about the same time—I think in 1833-

Methinks I see him-

As I have already said in "The Peak and the Plain," and cannot say anything more to the purpose now, Pemberton, in his readings gave not only all that was worthy of his author, but so threw around the subject the light of his versatile genius, as to enkindle your own, —to awaken, ' the Shakespeare within you,' should it be one of Shakespeare's dramas -

Besides several lectures on some of Shakespere's greatest characters—of which I remember "Hamlet," "Lear," and “Shylock" best—he gave us some pleasant lectures on, and readings from , popular writers of the day. Indeed this lectures on Social Readin, with examples were perhaps as interesting as any. But his influence was by no means confined to the lecture room. Wherever he was a guest, the longer he staid, the more he was loved by all, for his bon homme, his pathos, wit, and fun. His racy anecdotes, his graphic descriptions, and his characteristic representations of people he had met in every part of the world, afforded an inexhaustible source of entertainment ; and of one of his of a remarkable rencontre he had with an old Indian chief, I deeply regret it is not in my power to give even an outline at all worthy of the subject. A description he also gave of an American camp meeting, and his portraiture of one of the preachers, it would be equally impossible adequately to follow him in. It was rich and rare in the extreme.

One day while in Nottinghamshire he took a stroll, with Willaim and Richard Howitt, to Annesley Hall, the sometime home of Mary Chaworth, and on the way they called at Hucknall Torkard Church to see Byron's tomb, where many years afterwards I read in the Album there, the autograph of " C R Pemberton, a Wanderer ;" but though "wanderer" he felt himself to be, be made that walk a hundredfold more interesting to those tasteful and thoroughly-

Sometimes he would foot it alone as far as the grand old remnant of Sherwood called Birkland, where to this day hundreds of oaks remain, the youngest of which will be six or seven hundred years old—and where some of those which have been felled had King John's cypher deep under the bark. He on took such a walk London, between the two lectures he was delivering to one of the metropolitan institutions, called in Nottingham by the way, and afterwards published a most original and beautiful description of the old wood (in the Monthly Repository for June, 1834), in which he calls it "a ruined Palmyra of the Forest."

But at Sheffield, as well as Nottingham, was Pemberton a frequent and welcome visitor. In all his wanderings there were few places in which he felt more at home ; for Sheffield (like old Nottingham in that respect) had a circle of the very people for understanding and loving such a man. Dwelling there in those days was a genial large-

Mr. Bridgeford's literary power was not great ; but he had the next great power, that of thoroughly appreciating it in others, and making them mutually known. It was quite enough for any intellectual stranger to find him out, and be instantly made no stranger at all to men of like mind in Sheffield. Whether it was owing to this, or to other introduction, I am not clear ; but I do know that there were few men anywhere to whom Pemberton felt more attached than to Bridgeford, while, as time went on, almost every person of mind and taste in the town and neighbourhood had begun to regard Pemberton almost as a kinsman ; and I had the assurance from Mr. Fowler that his friendly regard for me sprang first from manifest reverence and love for the Wanderer.

Yet, after all, it would be unjust to say that this feeling was confined to any locality. At Woodbridge, with Bernard Barton ; with Mary Russell Mitford, in "Our Village," near Reading ; with a gentleman named Elliott (then a farmer in the county of Durham, but now in Australia), just as with Mr. Flower at Stratford-

Between his return from Gibraltar and the autumn of 1838, Pemberton had been able to give a few lectures at Birmingham, Wisbeach, and Sheffield. Of his first lecture, on this occasion, a correspondent of the Independent said :-

The subject of the evening's lecture was Brutus, in Julius Caesar. He brought out, one by one, the beauties of the character, and when he made it appear, as it really is, a glorious specimen of the best qualities of human nature, he held it up for admiration and instruction, Pemberton was no longer the man he had been some short time before,—he had left all his own weaknesses and entered into the loveliness and truth of Brutus. The illustrated passages were given with the delicacy and power of former times. It was life in death, and showed how the vigorous soul can impart energy to the wasted body.

He lived on, however, for nearly a year and some portion of which he passed at the Pyramids, then returned and died, at Birmingham, in the house of a brother, whose daughters (one of whom was afterwards married to Anthony Young, the actor) kindly tended him to the last. I have heard it said (I think it was by Edward Robinson, who married another of his nieces) that Mr. G. J. Holyoake (then a very young man) was often with him in his closing days, and that one day Pemberton asked him to read a passage he pointed out in the New Testament—a passage gave him a solace beyond his power to express-

In the month of January, 1843, I stood in Key Hill Cemetery, near Birmingham, with Mr. Fowler (now also departed) and read, on a large flat stone, the following inscription, composed by the late Mr. W. J. Fox, who knew him well :

BENEATH THIS STONE

REST THE MORTAL REMAINS OF

CHARLES REECE PEMBERTON,

WHO DIED MAR 3, 1840, AGED 50.

His gentle and fervid nature,

His acute susceptibility,

And his aspirations to the beautiful and true,

Were developed and exercised

Through a life of vicissitude,

And often of privation and disappointment

As a public Lecturer

He has left a lasting memorial

In the minds of the many

Whom he guided to a perception

Of the genius of Shakespeare

In its diversified and harmonising powers.

At oppression and hypocrisy

He spurned with a force proportioned

To that wherewith he clung

To justice and freedom, kindness and sincerity,

Ever prompt to generous toil,

He won for himself from the world

Only the poet's dowry,

"The hate of hate, the scorn of scorn, The love of love ! "

Contributed by : Rachel